The find roughly doubles the number of known seamounts in Earth’s oceans. Satellite data reveal nearly 20,000 previously unknown deep-sea mountains.

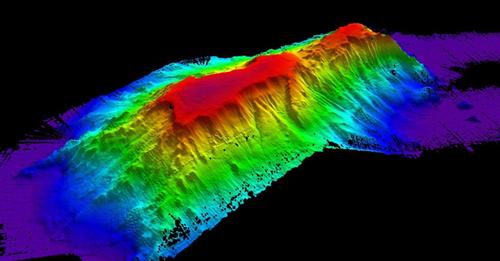

An elevation image of Kelvin Seamount, in a rainbow of color with purple at the bottom and red at the top, on a black background.

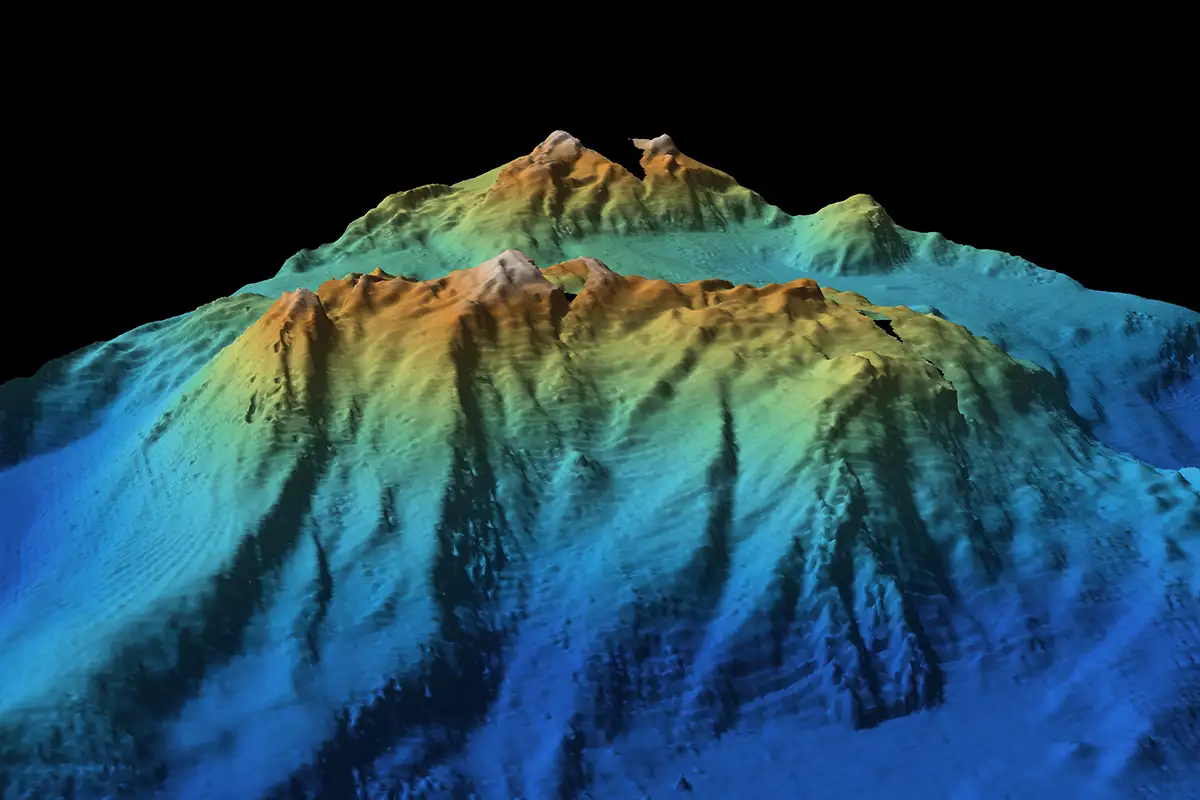

Ship-mounted sonar reveals how Kelvin Seamount, off the coast of Massachusetts, rises from the seafloor (purple and blue denote low elevation while red is high). A new mapping technique based on satellite data has found thousands of previously unknown undersea mountains.

The number of known mountains in Earth’s oceans has roughly doubled. Global satellite observations have revealed nearly 20,000 previously unknown seamounts, researchers report in the April Earth and Space Science.

Just as mountains tower over Earth’s surface, seamounts also rise above the ocean floor. The tallest mountain on Earth, as measured from base to peak, is Mauna Kea, which is part of the Hawaiian-Emperor Seamount Chain.

These underwater edifices are often hot spots of marine biodiversity (SN: 10/7/16). That’s in part because their craggy walls — formed from volcanic activity — provide a plethora of habitats. Seamounts also promote upwelling of nutrient-rich water, which distributes beneficial compounds like nitrates and phosphates throughout the water column. They’re like “stirring rods in the ocean,” says David Sandwell, a geophysicist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

The best of Science News – direct to your inbox.

Headlines and summaries of the latest Science News articles, delivered to your email inbox every Thursday.

More than 24,600 seamounts have been previously mapped. One common way of finding these hidden mountains is to ping the seafloor with sonar (SN: 4/16/21). But that’s an expensive, time-intensive process that requires a ship. Only about 20 percent of the ocean has been mapped that way, says Scripps earth scientist Julie Gevorgian. “There are a lot of gaps.”

So Gevorgian, Sandwell and their colleagues turned to satellite observations, which provide global coverage of the world’s oceans, to take a census of seamounts.

The team pored over satellite measurements of the height of the sea surface. The researchers looked for centimeter-scale bumps caused by the gravitational influence of a seamount. Because rock is denser than water, the presence of a seamount slightly changes the Earth’s gravitational field at that spot. “There’s an extra gravitational attraction,” Sandwell says, that causes water to pile up above the seamount.

Using that technique, the team spotted 19,325 previously unknown seamounts. The researchers compared some of their observations with sonar maps of the seafloor to confirm that the newly discovered seamounts were likely real. Most of the newly discovered underwater mountains are on the small side — between roughly 700 and 2,500 meters tall, the researchers estimate.

However, it’s possible that some could pose a risk to mariners. “There’s a point when they’re shallow enough that they’re within the depth range of submarines,” says David Clague, a marine geologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing, Calif., who was not involved in the research. In 2021, the USS Connecticut, a nuclear submarine, ran into an uncharted seamount in the South China Sea. The vessel is still undergoing repairs at a shipyard in Washington state.